Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

Addictions

Why the U.S. Shouldn’t Copy Canada’s Experiment with Free Drugs

By Adam Zivo

Harm-reduction activists claim evidence supports “safer supply,” but their studies don’t back that up.

Canada, where I call home, is the only jurisdiction in the world that hands out free addictive drugs to addicts. Under the “safer-supply” policy, Canadian health authorities distribute hydromorphone—an opioid as potent as heroin—as well as, to a lesser degree, oxycodone, pharmaceutical fentanyl, and mild stimulants. These drugs are provided at no cost and, until recently, rarely had to be consumed under medical supervision.

Some American harm-reduction activists claim that Canada’s experience—and studies of it—prove that safer supply saves lives. In reality, the studies they cite are deeply flawed. They rely on weak methodologies, including biased interviews and self-reported surveys, and fail to isolate the effects of safer supply from those of other interventions. U.S. policymakers should not let such shaky evidence justify similarly misguided policies at home.

Canada piloted safer supply in 2016 with no evidence that it worked. Some clinical trials suggested that administering pharmaceutical-grade heroin under careful medical supervision could stabilize severely addicted drug users. But advocates took this evidence and claimed that it supported their safer-supply experiment, despite crucial dissimilarities—the most important being the lack of witnessed consumption.

Over the following years, radical activist-scholars produced numerous evaluations and studies declaring that safer supply “saves lives” and improves recipients’ quality of life. As Canada expanded program access nationwide in 2020, policymakers latched on to this “evidence-based” experiment, condemning critics as anti-science.

This evidence is predominantly composed of qualitative studies, which rely not on data but on interviews with safer-supply recipients and providers. The interviewees naturally say that the program is wonderful and has few downsides. Advocates then frame these responses as objective evidence of success.

Notably, the studies never reach out to those who might provide negative evaluations of safer supply—doctors, addicts uninvolved with these programs, or individuals newly in recovery. Addiction experts throughout Canada have dismissed these studies as glorified customer testimonials.

Some studies involve surveys, converting patient responses into quantitative data that can be statistically analyzed. For example, the London InterCommunity Health Centre (LIHC), one of Canada’s leading safer-supply prescribers, publishes survey-based evaluations that claim approximately half of its patients reduced their fentanyl consumption after enrollment. This quantitative method does not change the unreliability of self-reported data, however, and there’s nothing that keeps patients from giving false answers if it suits their interests.

A 2024 study conducted by Brian Conway, director of Vancouver’s Infectious Disease Centre, indirectly validated these criticisms. The study distributed surveys to 50 of his safer-supply patients and then collected urine samples immediately afterward. Conway discovered that, while only 4 percent of these patients self-reported diverting (selling or trading) all their safer-supply hydromorphone, 24 percent had no hydromorphone in their urine. That suggests a significant portion of patients lied on their surveys.

A few studies use administrative health data to show that enrollment in federally funded safer-supply programs correlates with improved health outcomes. But these studies make no effort to determine whether the free drugs themselves are responsible. The real driver could be the extensive wraparound services the programs offer, such as housing assistance and access to primary care. It’s like giving an obese man a personal trainer and a daily slice of cake—and then, when he loses weight, crediting the cake.

Last year, the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) published a study in the British Medical Journal examining the health data of 5,882 drug users over an 18-month period between 2020 and 2021. The study found that individuals who received safer-supply opioids were 61 percent less likely to die over the following week than those who didn’t. This number rose to 91 percent for those receiving safer-supply opioids for four or more days in a single week.

Encouraging, right? But not so fast. When a team of seven addiction physicians reviewed the study, they discovered that the researchers misrepresented their data. Safer-supply patients are often co-prescribed traditional addiction medications, such as methadone and Suboxone, that have long been proven to reduce overdoses and deaths (these medications are often referred to as opioid agonist therapy, or OAT). The study data showed that safer-supply patients who did not also receive OAT medications were just as likely to die as those who did not get safer supply. In other words, the benefits that the BCCDC researchers touted were likely driven primarily by OAT, not safer supply.

The study data also showed no significant mortality reductions after one year of accessing safer supply. One wonders why the researchers chose to fixate on the one-week follow-up numbers.

Most recently, a study published in JAMA Health Forum found that, between 2020 and 2022, British Columbia’s safer-supply policy was associated with a 33 percent increase in opioid hospitalizations and no change to drug-related mortality. The researchers arrived at this conclusion by comparing the province’s publicly available health data with data from a control group made up of a handful of other Canadian provinces. The study raised further doubts about safer supply’s scientific basis.

Over the past two years, Canadian policymakers have openly, if reluctantly, acknowledged that safer supply is not as well-supported as they once claimed. British Columbia’s 2023 safer supply fentanyl protocols clearly state, for example, that “there is no evidence available supporting this intervention, safety data, or established best practices for when and how to provide it.” Similarly, the province’s top doctor released a report in early 2024 admitting that the experiment is “not fully evidence based.” Just last autumn, the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Matters acknowledged in a major presentation that safer supply is supported by “essentially low-level evidence.”

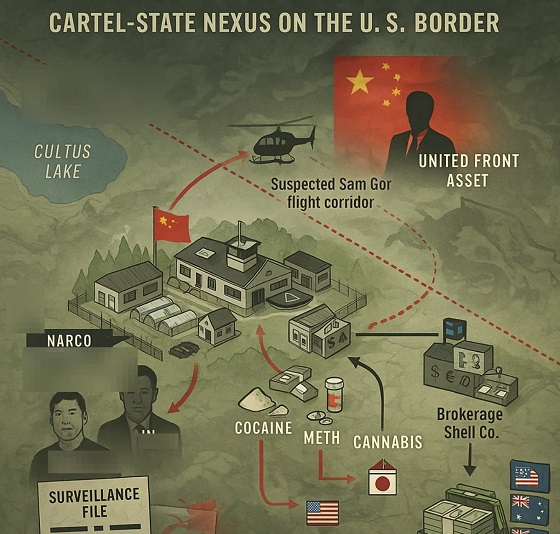

This about-face has been hastened by investigative media reports confirming that safer-supply drugs were being diverted to the black market, enriching organized crime and corrupt pharmacies in the process. Public support for the policy has apparently declined, as once-taboo criticism becomes normalized among Canadian politicians and commentators. The Canadian federal government has now quietly defunded its safer-supply programs (though independent prescribers still operate), while British Columbia mandated earlier this year that all safer-supply drugs be consumed under supervision.

Harm-reduction activists nonetheless maintain that the blowback against safer supply represents a “moral panic,” and that politics is overriding evidence-based policymaking. “Safer supply saves lives! Follow the science!” they insist. International policymakers, especially in the United States, should see through these misrepresentations.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Addictions

Field of death: Art project highlights drug crisis’ impact on tradespeople

City Counsellor Ron Kerr’s Blue Hat Memorial Project at the Tyee Spit in Campbell River, B.C., April 2025. | Courtesy of Ron Kerr

By Alexandra Keeler

The drug crisis is really a men’s mental health crisis, says Ron Kerr, the artist and city councillor behind a visually staggering project

Fifty thousand flags blanket the north end of Tyee Spit in Campbell River, B.C. — a staggering visual memorial to the lives lost in Canada’s opioid crisis since it was declared a public health emergency in 2016.

Called the Blue Hat Memorial Project, the installation spans nearly the length of a football field. It features 36,000 blue flags to represent the men and boys killed by toxic drugs, and 14,000 purple flags for women and girls.

“The actual installation does something you can’t do by just reading [about it],” said Ron Kerr, the artist behind the project. Kerr is also a city councillor in Campbell River, a city of 38,000 on the northeast coast of Vancouver Island.

“You’re visually seeing it, and it’s going right to your heart and creating an emotional response,” he said.

The installation’s name is a reference to the blue hard hats worn by newcomers or trainees on blue-collar job sites. Kerr says one of his aims is to draw attention to how the drug crisis has acutely affected working-class men. Between one-third and half of the individuals who died of opioid poisoning worked in the skilled trades, according to public health data.

Kerr, who has worked closely with tradesmen as an artist and advocate in men’s peer support groups, describes many of these tradesmen as “functional addicts” — employed, seemingly stable individuals who privately use drugs to manage pain or depression without others noticing.

“They are doing drugs at home or in their garage, and people don’t even know that they are [because] they’re functional, they’re working,” he said. “They’re able to control their depression or occupational injury through opiate drugs.”

Tradespeople are especially vulnerable to developing substance use disorders due to the physical demands, long hours and high injury rates associated with their work. Many use stimulants to stay alert or opioids to manage pain or cope with isolation in remote jobs.

“There is an expectation to get out the next day and get to work, no matter how you’re feeling,” said Kerr. “Self-medication is the easiest way to do it — a slippery slope from Tylenol to prescription drugs.”

A 2021 survey by the Construction Industry Rehabilitation Plan found that one in three B.C. construction workers reported problematic substance use. More than two-thirds screened positive for PTSD.

Loneliness is another major driver. Experts say men often avoid seeking help due to stigma, leading to further isolation.

“The opposite of addiction is connection,” said Kerr. “Men don’t have a place to go when they can’t deal with their issues, so they self-medicate.”

A pattern flipped

When Kerr first launched the installation in August 2024, he and a team of volunteers initially planted only blue flags. But in response to questions like, “Where are the women?”, he added purple flags this year.

“It was a blending — to give them their due,” he said.

Kerr’s installation sits on the unceded territory of the Liǧʷiłdax̌ʷ people, including the Wei Wai Kum Nation, a nation of nearly 1,000 people.

Wei Wai Kum’s chief, Chris Roberts, told Canadian Affairs he does not want the project’s focus on men to overshadow other key trends.

In B.C., Indigenous people die from drug poisoning at nearly seven times the rate of the general population. And within many Indigenous communities, the gendered pattern is at odds with national trends: women are dying at even higher rates than men.

“The opioid crisis has significantly affected my community as well, and it continues to — we are overrepresented as Indigenous people,” Roberts said.

“In our case, the gender split is much more balanced,” he added.

|

An aerial view of the Blue Hat Memorial Project in Campbell River, B.C., April 2025. | Courtesy of Ron Kerr

‘Inadequate recovery’

Currently, Campbell River — the overdose epicentre of northern Vancouver Island — has only one aging recovery centre.

“[The city is] a hub for the whole North Island, but we have very little in terms of recovery,” said Kerr. “[There is] just one inadequate recovery centre in a 50-60 year old house with tiny rooms.”

Kerr is critical of how B.C. has implemented harm reduction strategies. He says policies such as drug decriminalization and safer supply were launched without the recovery infrastructure needed to make them effective.

“[Portugal] legalized drugs too, but the most important thing was that they provided the recovery services for them — they went all in,” said Kerr. “In this province, they just haven’t spent the money and time on doing that.”

Kerr also worries too many resources have gone to safer supply programs, without offering drug users a way out.

“When you get a person in full-blown addiction, and you’re giving them all the drugs they need, the food they need, and the clothes and shelter, what’s going to stop them from carrying on?” he said.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Kerr wants his installation to draw attention to the need for more recovery-oriented solutions, such as treatment centres and housing. In particular, he points to a lack of affordable or free housing for people to live in after initial recovery.

“What you need is a good, clear off-ramp,” said Kerr. “They need to have recovery options that are either affordable or free so they can get off the road that they’re on.”

Chief Roberts agrees. Wei Wai Kai Nation is currently converting the former Tsạkwạ’lutạn resort into a 40-bed healing centre that will combine medical care with culture-based recovery.

“We’ve made investments to acquire properties and assets where people can go and reconnect with the land, the territory and their identity as a Ligwilda’xw person,” Roberts said.

Kerr says he will consider the Blue Hat Memorial a success if it leads to more funding and momentum for these types of recovery-oriented services.

The Blue Hat Memorial remains in Campbell River until the end of April. But Kerr, who previously re-created the installation in Nanaimo and West Vancouver, says he remains committed to doing more projects.

“I’ve got no expectation of senior government to come along and do this without a groundswell of grassroots people saying ‘we need this,’ and pushing government to do it,” said Kerr.

“I’m going to keep having the installation until that happens.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe ESG Shell Game Behind The U.S. Plastics Pact

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoBongino announces FBI will release files on COVID cover up, Mar-a-Lago Raid and more

-

Great Reset1 day ago

Great Reset1 day agoThe WHO Pandemic Treaty could strip Canada of its ability to make its own health decisions

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoCarney government’s housing plan poses major risks to taxpayers

-

espionage1 day ago

espionage1 day agoPro-Beijing Diaspora Group That Lobbied to Oust O’Toole Now Calls for Poilievre’s Resignation Amid PRC Interference Probes

-

espionage20 hours ago

espionage20 hours agoOttawa Raises Alarm With Beijing Over Hong Kong Detention of CPC Candidate Joe Tay’s Family

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoFreedom Convoy leader Tamara Lich to face sentencing July 23

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoTrump’s surgeon general pick is a threat to Big Pharma, not medical freedom